Everyone knows about the pottery tradition of Vietri sul mare, but few yet know that there is a clay hill in Salerno whose mining and processing predates Vietri's by millennia. Rufoli is the mother-land from which the potters of the coast draw the raw material to make it manufactured. The ancient kilns for the production of "riggiole" constitute the typological element that characterizes this site.The entire hill from Brignano to Ogliara has always been destined for the extraction and processing of clay, since very remote times .Traces of clay processing have already been found in the ancient Etruscan-Samnite necropolis of Fratte. Thus pottery has always been seen as an integral resource in an agricultural-based economic circuit. For centuries, terracotta represented the basis of local building, and it was from those semi-finished bricks that the Vietri sul Mare ceramics school originated, enlivened in the 1920s and 1930s by the contribution of German artists, who laid the foundations for the Vietri decorative style. After World War II, activity resumed in Rufoli, but in a rapidly changing technological landscape. Rufoli's bundle furnaces suffered a profound crisis. As early as the late 1950s, and in the following decade, new, cheaper bricks took the place of traditional artisanal bricks. Produced on an industrial scale (also in the area, for example by D'Agostino, the market leader in the sector until those years), they supported the building boom of those years more economically. The overall volumes of handicraft production contracted sharply and there was a move toward specialization in tiles and tiles. Planimetrically, a kiln is configured as an enclosed, quadrangular enclosure, placed along a path and bordering the countryside. The construction technique generally favors tuff. Instead, the use of terracotta is predominant in the formal definition of openings or closures. Now almost all abandoned, the kilns stand near the large quarry that expands from the core of Rufoli to the slopes of the Giovi hill and the valley towards Brignano. Immediately abutting the church of St. Michael are the ruins of the Della Rocca furnace. Next, located along the road through Rufoli, are the Soriente furnaces and further on, connected to the present De Martino furnaces, what remains of the Ventura property.

The Faggot Furnaces

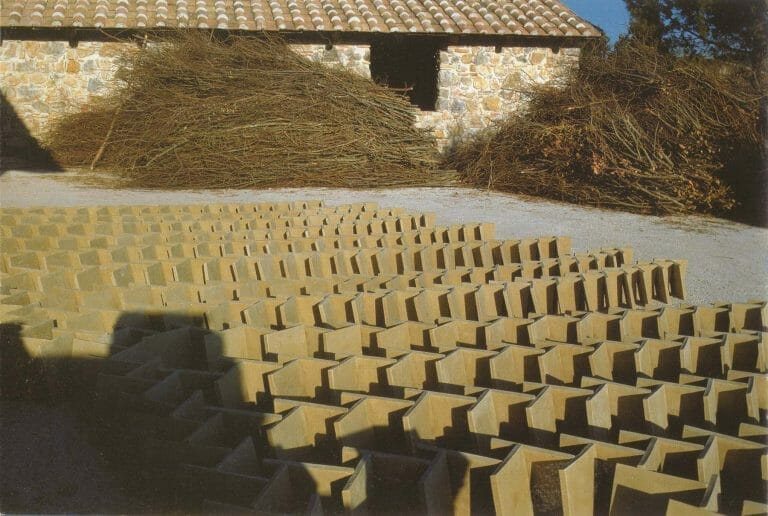

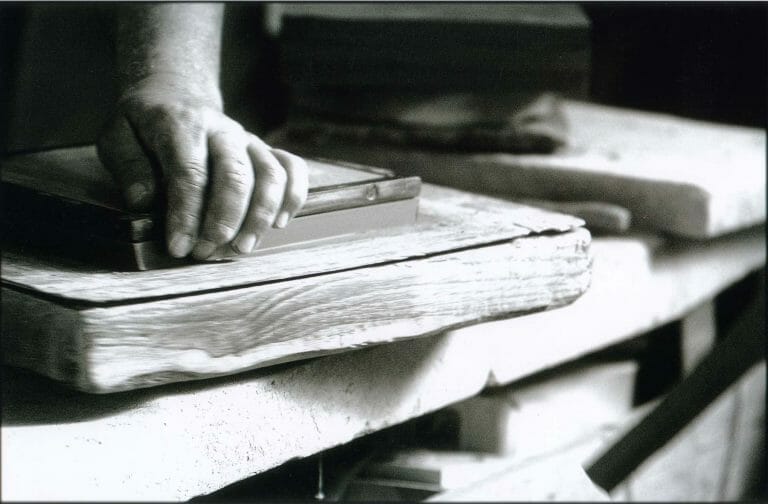

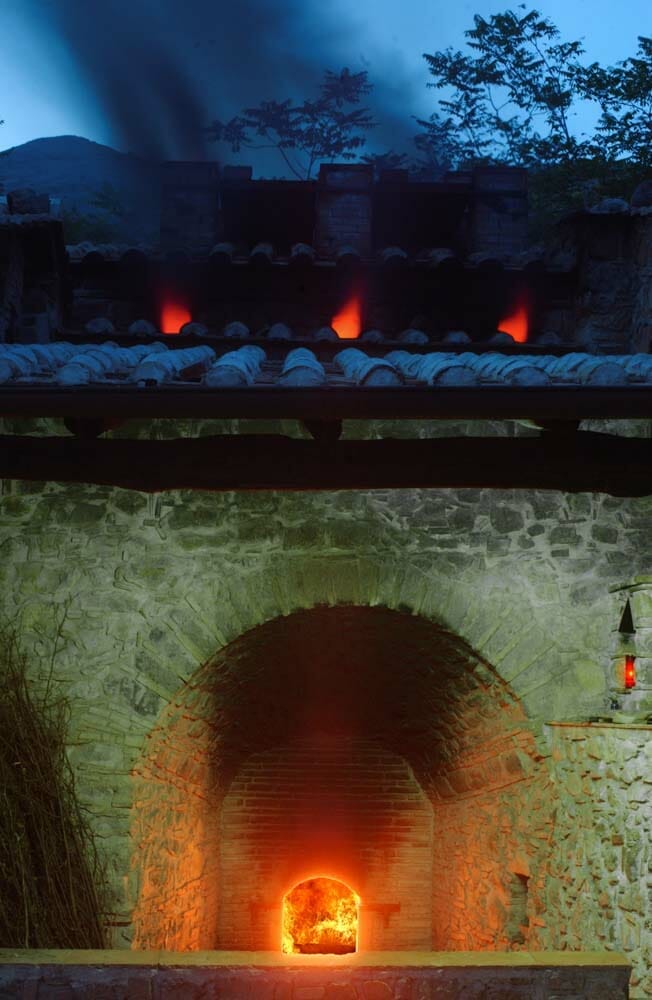

Kiln time is marked by the repetition of ever-changing gestures. Blocks of clay are pressed and shaped. The resulting forms are stacked and covered with sacks so they do not dry out. Trimming takes place on a wooden bench. The clay cuttings (trimming) fall into the wheelbarrow, in front of the scanno, and will be partly used as spacers in the loading of the kiln. The long and delicate process of drying begins. Next they are exposed to the sun in a herringbone or palombella pattern. One is finally ready to load the kiln. It takes four days of work. Baking takes 36 hours. The baked tiles are arranged in a cross pattern to circulate the fire. Along the walls of the kiln, to circulate the flames, pieces of fired bricks are placed. Wedges of dried clay are placed between the tiles. Once the kiln is loaded, the doors are closed with bricks; the holes are sealed with malleable raw clay, leaving a peephole with a view in gray tuff. Fire is apparently free to burst in with its life energy. In reality it is man who drives it by spying it, to bend it to his own need. Thousands of bundles are gathered for immolation. The fire blazes in the ditch with the crackling and chanting of wood: a scent of underbrush, of burnt laurel, spreads in places, uneven and sudden. It is the incense of the ritual perpetuated under the image of St. Antuono, to whom a lamp is offered to burn for the duration of the cooking. The baker allows himself no pause; watchful eyes scrutinize the color and sound of the flame. Black smoke escapes from the peepholes: a sign that the condition of the clay is changing. Gradually there is the transition from the gray of the molded material to the different shades of fired clay, gilded by fire. The labor is completed. The riggiole are chiseled by the squarer. They are made to sing: the somber sound is a sign of faulty firing.

The De Martino Furnace

The De Martino family has been working and producing handcrafted terracotta since 1479, as stated in a notarial document kept at the Benedictine Abbey of Cava de' Tirreni, proving its distant origin; a work based on manual skills that has been handed down for centuries. As described in the previous paragraph, it is the same ritual of the past. Even today it is possible to see the entire production cycle by visiting the only furnace that survived the massive industrialization that began in the 1950s: shaping, firing and squaring. After the manual steps, the tile arrives in the kiln, and it is there that the mystical experience of firing takes place. The furnace is closed and blessed, by impressing a cross on the concrete of the newly walled door. The terracotta from the De Martino furnace can be said to be a timeless, noble material. It can be seen in the ancient palaces of Rome, such as Villa Doria Pamphili, but also in modern structures such as the luxurious Bryant Park hotel in New York City.

There are three main products: classic terracotta made with an exclusively clay mixture that gives the tile the terracotta color. Its surface appears a little wavy. Colored terracotta is a mix of clay, oxides and dyes. The possibility of customization is maximum. The decorated terracotta is instead a “riggiola” (floor tile) glazed and decorated by hand according to the Campania tradition.

Women of the Furnace

The workers and managers of the kiln have mostly been men, the De Martino brothers being Antonio, Luigi and Tommaso, but there have been women in the past who have dedicated themselves to some phases of production, particularly hand molding. This operation, which involves pressing clay into a wooden mold and then making the surface smooth, was performed from the postwar period until the 1990s by Teresa Avagliano, the mother of the current De Martino managers. Subsequently, it was from 1998 until 2004 that another woman worked as director of the decoration workshop, bringing new ideas and new forms: this was architect-ceramicist Sofia De Mas, who in 2003 brought her creative workshop from Rufoli to Positano for the Cartoon on the bay event. The workshop was held en plein air with filmmakers, cartoonists, illustrators, actors participating in the festival that flowed into the 2003 Open Doors exhibition. Later, Nathalie Figliolia also did her experiments in decor and innovative colors there.

Another artist who has worked at the Fornace is Patrizia Grieco, organizer of various events including Ogliara - Paris - Ogliara (2014-2015), which saw an exchange between two artists, Grieco herself and French painter and former television director Jean-Pierre Duriez. The event made it possible to raise awareness of Rufoli's cotto in France. The exhibition of Jean-Pierre's inspiring paintings and Grieco's sculptures was held in the Centre Danmark on the Champs Elysées in Paris.